| Thursday, 05 September 2013 14:51 |

On

August 27, 2013, Indigenous and environmentalist activists took to the

streets of Ecuador to protest against a reversal in government plans not

to drill for oil in the ecologically sensitive Yasuní National Park in

the eastern Amazon basin. On

August 27, 2013, Indigenous and environmentalist activists took to the

streets of Ecuador to protest against a reversal in government plans not

to drill for oil in the ecologically sensitive Yasuní National Park in

the eastern Amazon basin.

The protests came after Ecuadorian president Rafael Correa announced on August 15 the failure of his Yasuní-ITT initiative.

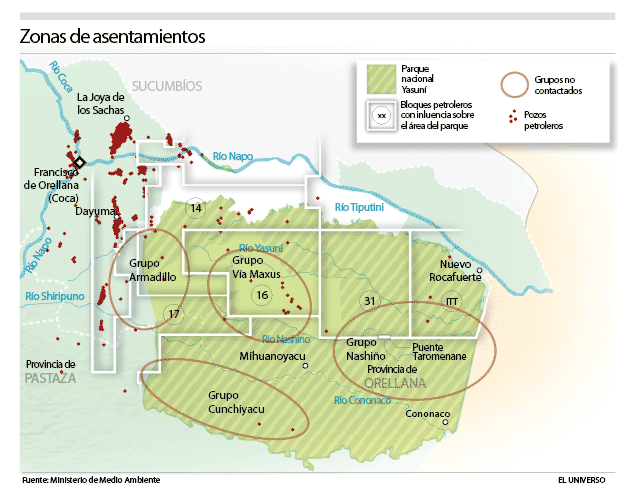

Experts

estimate that the Ishpingo Tiputini Tambococha or ITT oilfields in the

Yasuní National Park hold nearly one trillion barrels of oil, about

one-fifth of Ecuador’s total reserves. Its extraction could generate

more than $7 billion in revenue over a 10-year period.

UNESCO

designated the park as a world biosphere reserve in 1989 because it

contains 100,000 species of animals, many which are not found anywhere

else in the world. Each hectare of the forest reportedly contains more

tree species than in all of North America.

Not

drilling in the pristine rainforest would both protect its rich mix of

wildlife and plant life and help halt climate change by preventing the

release of more than 400 million tons of carbon dioxide into the

atmosphere.

According to the Yasuní-ITT

plan, in exchange for forgoing drilling in the park, international

donors would contribute $3.6 billion, half of the estimated value of the

petroleum, to the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) for health

care, education, and other social programs.

Despite

broad local and international support for the plan, donors were not

forthcoming with contributions. After six years, the fund had only

collected $13 million in donations with $116 million more in pledges.

“The

world has failed us,” Correa stated in a nationally televised news

conference in which he announced that he had signed an executive decree

to permit exploitation of oil in the Yasuní. “With deep sadness but also

with absolute responsibility to our people and history, I have had to

take one of the hardest decisions of my government.”

Correa

blamed the world’s hypocrisy for failing to support the innovative

proposal with financial donations. “We weren’t asking for charity,”

Correa said, “we were asking for co-responsibility in the fight against

climate change.”

The initiative was one of the government’s most popular, and enjoyed support of 90 percent of the Ecuadorian population.

Despite

being a signature program of Correa’s Citizens’ Revolution, the

proposal not to drill in the ecologically sensitive area of eastern

Ecuador predated his government. The idea to leave oil underground in

exchange for raising funds as part of an ecological debt of

industrialized countries was an initiative of Indigenous movements and

environmentalists. In 2007, Correa incorporated those ideas into his

government.

2008 Constitution

Many

opponents contend that Correa’s decision to drill in the Yasuní is a

violation of the country’s new and progressive 2008 constitution.

Ecuador’s constitution is the first in the world to recognize the rights of nature. Article 71 declares that “nature or Pachamama [the Quechua term for mother earth], from which life springs, has the right to have its existence integrally respected.”

In

addition to the constitutional mandate to protect the rights of nature,

the constitution also required the government to protect the rights of

Indigenous peoples, and in particular the Tagaeri and the Taromenane who

are living in voluntary isolation in the Yasuní National Park.

Article

57 of the 2008 constitution specifically states that “the territories

of the peoples living in voluntary isolation are an irreducible and

intangible ancestral possession and all forms of extractive activities

shall be forbidden there.” The article concludes, “the violation of

these rights shall constitute a crime of ethnocide.”

Critics

maintained that Correa’s decision to drill in the Yasuní was a direct

violation of the constitution, and furthermore an act of ethnocide.

CONFENIAE

The Confederación de Nacionalidades Indígenas de la Amazonía Ecuatoriana

(CONFENIAE, Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorian

Amazon) released a statement on August 20 that denounced the

government’s plans to terminate the Yasuní-ITT initiative. CONFENIAE

groups 21 organizations and federations from 11 Indigenous nationalities

in the Amazon.

“The

deepening of the extractive policies of the current regime, which

exceeds that of former neoliberal governments,” the statement reads,

“has led to systematic violations of our fundamental rights and has

generated a number of socio-environmental conflicts in Indigenous

communities throughout the Amazon region.”

CONFENIAE

points to a historical pattern of the extermination of Indigenous

groups due to petroleum exploration, including the Tetete in

northeastern Ecuador 40 years earlier. “History repeats itself,” the

federation proclaimed. “We are on the verge of a new ethnocide.”

The

current abuses occur, CONFENIAE complains, even as the country projects

an image as “possessing one of the world's most advanced constitutions,

which recognizes the collective rights of Indigenous peoples,

especially their right to free, prior and informed consent, the rights

of nature, the Sumak Kawsay, among others.”

Nevertheless,

“when the interests of large capital become involved, the rulers

through their control of the judicial system, demonstrate that they have

no qualms with reforming laws to legalize theft, looting, and human

rights violations.” CONFENIAE believes that Correa’s announcement to

suspend the Yasuní initiative “has been only one more example of the

neoliberal , pro-imperialist, and traitorous character of the current

regime.

From

CONFENIAE’s perspective, Correa’s actions confirmed what they had long

understood: “the government was never really committed to the

conservation of nature, beyond an advertising and media campaign to

project an opposite image to the world.” The government always had a

double standard, and plans to drill in the Yasuní was always the ace

that they held up their sleave.

Correa Correa

In

response to these criticisms, Correa denounced “Indigenous

fundamentalists” and leftist environmentalists, and argued, “the biggest

mistake is to subordinate human rights to ostensible natural rights.”

Correa

claimed that “the real dilemma” of drilling in a sensitive ecological

area is “do we protect 100 percent of the Yasuní and have no resources

to meet the urgent needs of our people, or do we save 99 percent of it

and have $18 billion to fight poverty?”

Correa

also contended that with modern technology it was possible to drill

with a minimal impact on the environment. He argued that drilling would

affect less than one-tenth of one percent of the park, and that it would

take place far from the “untouchable zone” where the the Tagaeri and

the Taromenane lived.

As

a neo-Keynesian economist trained at the University of Illinois at

Urbana-Champaign, Correa attempted to use petroleum resources to develop

the Ecuadorian economy. Correa maintained that anything could be used

for good or evil, and that he was determined to use Ecuador’s natural

resources to create a positive development model.

Creating

alternatives to an extractive economy was a long-term proposition,

Correa said, and short-term dependence on mining for revenue and

employment was unavoidable. He repeatedly declared that “we can’t be

beggars seated on a sack of gold” to justify the exploitation of oil and

other minerals.

Many

environmental activists disputed Correa’s contention that oil could be

extracted from Yasuní with minimal damage. These critics contend that

roads and other infrastructure associated with any drilling operation

inevitably would open up the park to colonists and result in

irreversible damage to the ecosystem.

At

best, Correa always provided at best tenuous support for the Yasuní

proposal. He repeatedly threatening to move to a “Plan B” to commence

drilling in the preserve if donations were not forthcoming. Reports

indicated that quietly, and behind the scenes, the Ecuadorian government

was proceeding at full speed to develop the oil fields because of the

their significant economic potential.

During the 2013 presidential campaign, Alberto Acosta who ran for the top office with the Coordinadora Purinacional por la Unidad de las Izquierdas

(Plurinational Coordinating Body for the Unity of the Left), said that

“if Correa wins the ITT initiative will be dropped. The infrastructure

is already in place to exploit the oil.”

Indicative

of Correa’s ultimate commitment was placing Ivonne Baki, a conservative

politician who had participated in previous neoliberal governments, in

charge of the Yasuní project.

Resource curse

Critics

have long referred to petroleum as a “resource curse.” The value added

to the processing of raw commodities accrues to advanced industrial

economies, not to Ecuador. Furthermore, as Ecuador raised taxes on oil

companies the companies stopping investing in new explorations and

production stagnated at about 500,000 barrels per day.

Serious

questions remain whether a reliance on export commodities could ever

grow Ecuador’s economy. A common saying in Ecuador was that country

became a dollar poorer for every barrel of oil that it exported.

Leftist

opponents repeatedly charged that Correa had failed to make a

fundamental break from a capitalist logic of resource extraction.

Sociologist Jorge León Trujillo states that he never understood how the

commodification of the environment, as would happen with the Yasuní

initiative, could be considered a revolutionary proposal.

The

economic proposals that Correa pursues are not unlike those that the

conservative economist Hernando de Soto in neighboring Peru has long

advocated. At best, for leftists Correa’s approach appeared to be one of

green capitalism that was quickly discarded when it no longer provided

the expected economic returns.

Referendum

On

August 22, in the name of Indigenous, student, and environmental

organizations, the noted jurist Dr. Julio César Trujillo formally

delivered a request to the constitutional court in Quito for a popular

referendum on the president’s plans to drill in the ecologically

sensitive park.

To

demand a referendum, proponents need to collect 584,000 signatures, or 5

percent of the voters in this country of 15 million people. If enough

signatures are collected, voters will be asked: “Do you agree that the

Ecuadorean government should keep the crude in the ITT, known as block

43, underground indefinitely?”

Correa

welcomed the challenge of opponents calling for a referendum on the

government’s decision to drill in the Yasuní. “How am I going to oppose a

referendum if it is a constitutional right to request one?” Correa

stated on August 27. “It is also my right to request congressional

permission” to drill for oil in the park, he declared.

Correa’s petition to drill in the Yasuní declares that it is in the “national interest” to do so.

Correa’s

party Alianza PAIS has a super majority in a congress that has been

compliant to his leadership; there is little question that it will

approve his drilling proposal. “We are sure,” Correa declared, “that

with sufficient information we will have the full support of the

Ecuadorian people.”

Conservatives

Correa’s conservative opponents did not hesitate to use the failure of the Yasuní plan to attack the Ecuadorian government.

Writing in the opposition Quiteño newspaper Hoy,

José Hernández criticized Correa for putting the project in the hands

of Baki, a person “whose ecological past is as irrefutable as her

enormous political convictions.” Correa, according to Hernández, sent

the wrong message by putting such an important political project in the

hands of a person whose political positions shifted so easily with the

prevailing winds.

The New York Times

editorial board questioned whether Correa’s original plan was “a

good-faith effort to preserve an extraordinarily rich and diverse

ecosystem.” The newspaper argued that “the consequences are dismal” and

that “a valuable model for protecting regional biodiversity hot spots

through a kind of global stewardship has been jettisoned.”

Given

the previous editorial stances of these newspapers in criticizing the

Correa administration for its alleged repression of freedom of the

press, the hypocrisy and opportunism of these editorial stances that now

apparently advocated an environmental perspective was immediately

obvious.

Correa

tweeted, “now the biggest environmentalists are the mercantilist

newspapers.” He sarcastically suggested a referendum to require that

newspapers be published digitally in order “to save paper and avoid

indiscriminate logging.”

Protests Protests

Meanwhile, Correa’s leftist opponents continued to protest his decision to drill in the park.

At

the Plaza de la Independencia in front of the presidential palace in

Quito on August 27, pro-Yasuní protesters met a counter-demonstration of

supporters of Correa’s ruling party Alianza PAIS.

Police

fired rubber bullets on the protesters, hurting twelve people and

detaining four. Among those detained was Marco Guatemal, vice-president

of Ecuarunari, the powerful federation of Kichwa peoples in the

Ecuadorian highlands that has long fought against neoliberal economic

policies.

The crackdown on the Yasuní demonstrators is part of a broader pattern of the criminalization of social protest in Ecuador.

Three

days before Correa announced his withdrawal from the Yasuní agreement, a

court in the southeastern province of Morona Santiago sentenced Pepe

Luis Acacho, a congressional deputy for the Indigenous political party

Pachakutik, as well as Indigenous leader Pedro Mashian, to twelve years

in prison on charges of “sabotage and terrorism” for leading a protest

against a proposed water management law in September 2009.

This

case came on the heels of an April 2013 sentence against Pachakutik

deputy José Cléver Jiménez Cabrera and former union leader Fernando

Alcibíades Villavicencio Valencia to 18 months in prison for slandering

Correa in the aftermath of a September 30, 2010 police protest.

Under

Correa’s government, hundreds of activists face terrorism charges,

largely for organizing protests against extractive policies. Some

observed that social movements had not faced this level of repression

under previous neoliberal governments.

In response to the repression, the Confederación de Nacionalidades Indígenas del Ecuador (CONAIE,

Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador), the country’s

primary Indigenous organization, released a statement that demanded

“that the president stop the repression and prosecution of Indigenous

leaders and convoke a referendum on oil exploration in the ITT.”

|

Dedicated to the Rescue, Rehabilitation, Rehoming of Rottweilers. We are a Holistic Non Profit Rescue Sanctuary in Washington state. Welcome to our Blog, a safe, gentle place to share with, learn from and sound off on topics of interest to you and your animals, we are all related and come in a variety of shapes & sizes. Subjects interests are Animal Rights, herbs, respect of the natural world, indigenous populations and the truth. Let's see where our journey will lead us.

Thursday, September 26, 2013

Ecuador Rights Of Nature Threatened

Labels:

Activist,

Animals,

Ecuador,

environment

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment